The Half-Life of Moral Outrage on Social Media

Written by JP Kloppers, CEO DataEQ

On June 8th 1972, a young Associated Press photographer, Nick Ut, captured the iconic image of a nine-year-old Vietnamese girl, Phan Thi Kim Phuc, fleeing her burning village after a misdirected napalm attack. The image hit the front page of the New York Times and deeply humanised the conflict for millions of Americans who previously had no real emotional connection to the plight of the local inhabitants in Vietnam.

Forty years on and the media landscape has altered fundamentally. Not only is a far greater volume of news generated on a daily basis, but it is available through a far greater number of conduits – some curated (newspapers, magazines and news sites) and some algorithmically driven (social media).

The latter channel – the social media news feed – is becoming an increasingly important primary news source for many. The Reuters Institute recently published its 2016 Digital News Report; among the findings were that, of respondents from a sample of 26 countries, half (51%) said they used social media as a source of news each week. Around one in ten (12%) claimed it to be their main news source. http://www.digitalnewsreport.org/survey/2016/overview-key-findings-2016/

Uniquely, on platforms such as Facebook, issues of general or humanitarian interest must, for the first time, compete side by side with news of personal relevance. Moreover, social media users are ever more deeply embedded in both the generation of news and commentary around it – and not merely within the private/personal spheres. Anyone with a camera phone can now record and document news of global significance; anyone viewing an image or story on a feed can comment or share it freely.

The result has been not only an exponential increase in the volume of news items and public participation in the generation thereof, but the creation of a massive amount of public sentiment metadata – records of social media commentary centred on everything from political candidates to wars and conflicts. Never before has it been possible to gain insight into how such a vast proportion of the public think and feel.

A social media study of the Syrian refugee crisis

Having raised questions around not only what constitutes an appropriate national response to emergent humanitarian issues, but also – more broadly – those concerning boarder security and immigration, the Syrian Civil War and the ensuing refugee crisis have been at the epicentre of widespread debate. Social media has been the focus of a substantial volume of the conversation.

According to World Vision figures, the scale of the crisis is immense. Nearly six years after the start of the civil war (in March 2011), the conflict has left 13.5 million people in need of humanitarian assistance. Among these are nearly five million refugees seeking shelter in both the Middle East and Europe and approximately six million who are displaced within the country itself. A substantial proportion of those affected by the conflict are children.

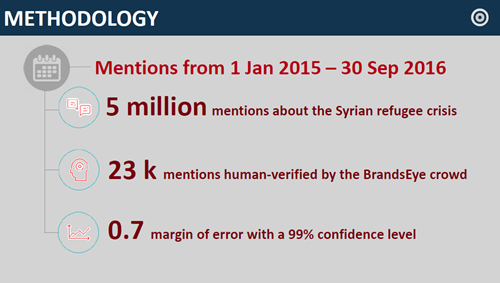

To better understand the role that social media has played in the crisis – particularly as a hub of debate, discussion and the expression of sentiment we analysed crisis-related social media discussions taking place from 1 January 2015 to 30 September 2016, a dataset encompassing five million individual mentions.

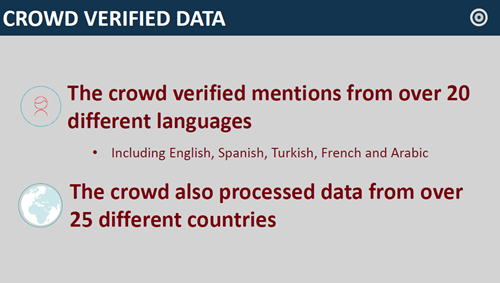

Of the total mentions, a smaller subset of 23,000 (in 20 different languages, stemming from over 25 countries) were human verified by the Crowd – a group of contributors trained to analyse and rate posts for sentiment, relevance and topics, a process that substantially increases the accuracy of standalone algorithmic analysis. Using this methodology, a high degree of accuracy and reliability was achieved in the results – a 0.7% margin of error with a 99% confidence level.

Key issues analysed over the period included the strength and duration of the story- or image-related sentiment (including, at the extreme, the expression of what may be termed ‘moral outrage’ – particularly strong reactions to photographs or stories), overall conversation volume and, crucially, levels of donations made to the cause

Sentiment by country and audience activity

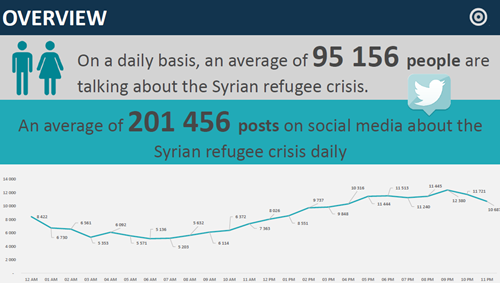

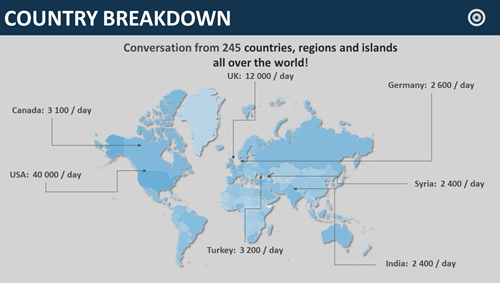

On average, it was estimated that over 95,000 social media users were talking about the crisis on a daily basis over the study period, creating over 200,000 new posts per day. Of the 245 countries, regions and islands in which conversations were taking place, American authors contributed by far the largest share: 40,000 new posts per day, as opposed to the UK’s 12,000, Turkey’s 3,400 and Germany’s 2,600.

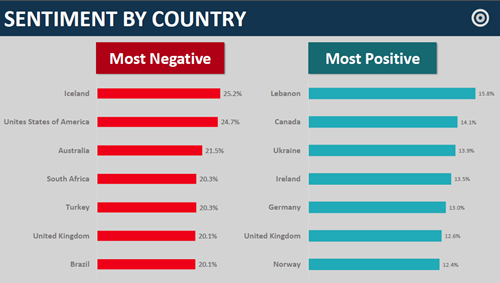

A particular area of focus was the degree to which attitudes towards the Syrian refugee crisis vary by country. Among the countries studied, sentiment was found to be most negative in Iceland, followed by the US, Australia, South Africa and Turkey. Chatter stemming from Lebanon, Ukraine, Ireland, Germany and Norway, by contrast, was found to be among the most positive, while the UK was ranked as one of the most highly polarised – among the top ten countries for expressions of both positive and negative sentiment.

Further differences registered at the extremes, where sentiment was vastly more negative than it was positive. Even where positive sentiment was highest – in Lebanon – it reached only 15.8%. In Iceland, by comparison, unfavourable comments topped 25%. In the five countries that ranked behind it, negative sentiment exceeded 20% in all.

The death of Alan Kurdi

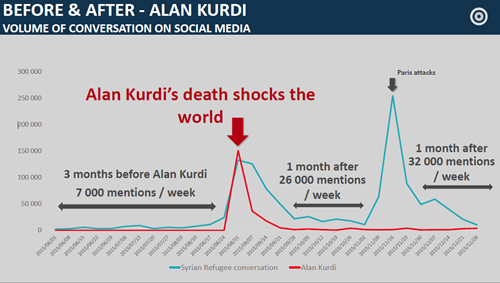

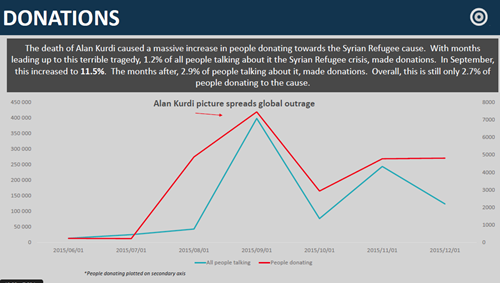

Among the news stories associated with the refugee crisis, that of the drowning of three-year-old Alan Kurdi in September 2015 was one that particularly inflamed social media. Not only did overall conversation levels and expressions of moral outrage spike around the issue, but the increased uptake was coupled with a strong increase in donations towards the Syrian refugee cause.

As a baseline, we estimated that there were an average of 7,000 mentions of the Syrian refugee crisis per week prior to Kurdi’s drowning. 1.2% of people talking about the crisis at this time were making donations. In the month of September, however, the figure increased sharply – 11.5% of people talking about the issue donated. In the months that followed, the figure fell back again to a mere 2.9%. The overall volume of conversation remained elevated, however, with an average of 26,000 crisis-related mentions per week

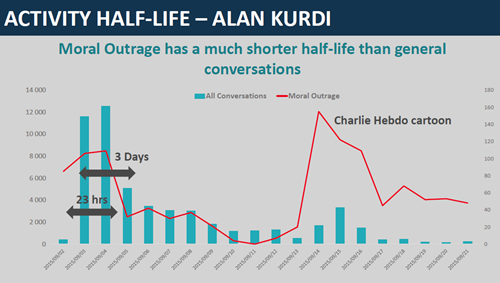

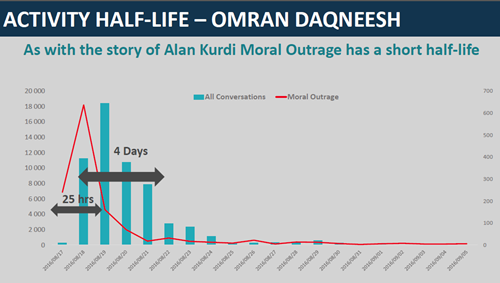

Crucially, the study found that expressions of moral outrage at the incident had a far shorter half-life than did general discussion. Having remained elevated between September 2-4, by September 5, outrage had already started to decline significantly. A little over a week later and very little still registered on social media.

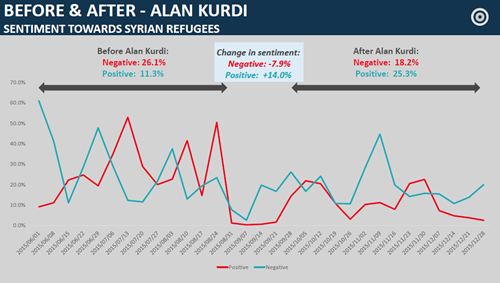

Importantly, the incident had a tangential (and lasting) effect on perceptions of the crisis. In the three months leading up to the death of Alan Kurdi, 26.1% of sentiment towards Syrian refugees was negative, while 11.3% was positive. The three months following the incident saw a dramatic reversal, however, with negative sentiment falling by nearly 8% to 18.2%, and positive sentiment more than doubling to 25.3%.

The story of Omran Daqneesh

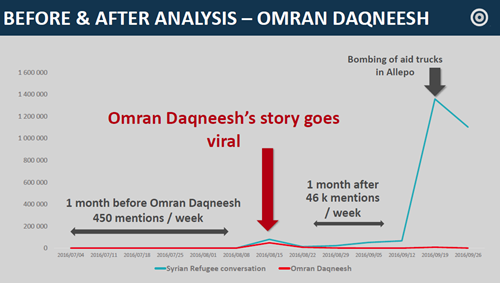

Nearly a year after the drowning of Alan Kurdi, new footage surfaced which rapidly gained attention across both social and traditional media platforms. At the centre was five-year-old Omran Daqneesh, who, bloodied and covered in powder, had been rescued from his home in Aleppo after an airstrike and placed in an ambulance by a rescue worker. The footage captured him seated, looking at the camera and touching a hand to his bloodied face.

As with the story of Alan Kurdi, the period of moral outrage following the airing of the footage was intense, but brief – a mere 25 hours saw social media activity peak sharply then fall. As before, the volume of all conversation related to the crisis remained elevated for slightly longer – approximately four days. The effect on overall mentions of the crisis, however, lingered: in the month leading up to the footage, there were 450 mentions of the Syrian crisis per week; the month after saw volume increase more than 100-fold, to 46,000.

November 2015 Paris attacks

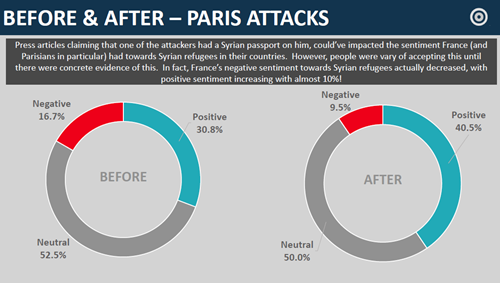

Another series of events sending shockwaves across the media were the November 2015 Paris attacks. The tragedy became linked to the refugee crisis when certain press reports claimed that one of the attackers had been found with a Syrian passport.

While such reports had the potential to affect French sentiment towards refugees adversely, we found that levels of negative French sentiment towards refugees in fact decreased after the attacks – from 16.7% to 9.5%. On the other hand, positive sentiment increased – from 30.8% to 40.5%. Neutral sentiment remained largely unchanged, shifting only 2.5%, from 52.5% to 50.0%.

Implications of the study

One of the study’s primary findings was the high degree of correlation (r = 0.8) between social media conversations around the crisis and donations to cause – both of which peaked suddenly and sharply with emergence of particular stories and images. Crucially, however, the study’s second finding was that this period of substantially elevated conversation volume, expressions of moral outrage and increased donation had a very brief half-life, lasting only a couple of days and decaying shortly after.

Given the extremely high levels of information to which social media users are exposed on a daily basis – and under which issues of general or humanitarian interest must compete side by side with news that is personally relevant to users – the emotional resonance of even very poignant stories appears to be relatively short – a few days at the outside. While overall conversation volume remains elevated for longer, donations spike with viewers’ initial reactions.

Moreover, given that algorithms underlie what topics crop up in personal social media news feeds (a subject around which there has been some recent controversy and allegations of manipulation), stories are selected merely to maximise user-specific relevance and interest. As such, even noteworthy issues tend to fade from view quickly, crowded out by both personal news and other more recent global events.

In the case of conflicts and crises, the above underscores why it is imperative for aid organisations to both gauge public perception and act rapidly within the period during which stories and images rise to prominence.

24 to 48 hours represents the window in which fund-raising efforts are likely to have maximal impact.